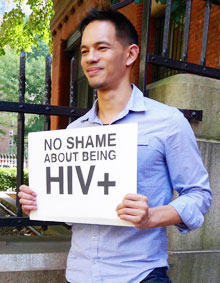

Laurindo GarciaFilipino HIV advocate Laurindo Garcia is the founder and chief executive of B-Change, an international social enterprise group aiming to promote social change through technology, with a focus on engaging and advocating for young LGBT in the Asia-Pacific. He is also a global ambassador for the ‘Here I Am’ campaign, which uses the voices and stories of people living with HIV to call upon world leaders to fully fund the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Garcia regularly speaks about his advocacy work and life as a gay man living with HIV at international AIDS events and conferences, including the 2012 and 2014 International AIDS Conferences.

Laurindo GarciaFilipino HIV advocate Laurindo Garcia is the founder and chief executive of B-Change, an international social enterprise group aiming to promote social change through technology, with a focus on engaging and advocating for young LGBT in the Asia-Pacific. He is also a global ambassador for the ‘Here I Am’ campaign, which uses the voices and stories of people living with HIV to call upon world leaders to fully fund the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Garcia regularly speaks about his advocacy work and life as a gay man living with HIV at international AIDS events and conferences, including the 2012 and 2014 International AIDS Conferences.

TREAT Asia Report: HIV rates are rapidly rising among young men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender individuals in the Philippines and throughout the Asia-Pacific. What do you think advocates in the region should do on International Day Against Homophobia and Transphobia (IDAHOT), 17 May, and every day to combat the homophobia and transphobia that continue to fuel the spread of HIV?

Laurindo Garcia: There’s no one single way that homophobia and transphobia manifest themselves in Asia, there are multiple ways—I guess that’s the complexity of hate. But one is that it reduces the political will to fight HIV. While there may be tacit agreement among lawmakers that HIV is an issue, we’re not seeing the policy changes needed, and I think a big reason for that is some lawmakers think that LGBT people are immoral, and therefore they don’t act.

Also, LGBT people often cannot access education or employment, and this has a direct impact on their ability to stay healthy, get tested, or seek treatment. And finally, I think one of the most significant ways homophobia fuels HIV is by causing internalized homophobia, which has an impact on the way that people make choices. If you put yourselves in the shoes of a young person growing up in a remote part of the Philippines, or Southeast Asia, or greater Asia, and you’re not seeing a lot of positive images of LGBT people, you may ignore health messaging or not access services because you are afraid of being seen as different.

I think the simplest way to combat all this is still visibility. I know that not everybody has the ability to do this, but for people who are able to, coming out, speaking to your parents, speaking to your friends, letting people know who you are, letting them see your true self, is an incredibly powerful way to change hearts and minds. Because things aren’t going to change until we humanize these issues and people can see that LGBT issues and HIV issues are actually touching everybody in our communities.

Laurindo Garcia and his partner, Alan Seah, in Singapore

TA Report: Why did you decide to publicly come out as gay and HIV positive despite the stigma and discrimination?

Garcia: The thing that had prevented me from being more open about my HIV status was fear of not being able to see my partner, who lives in Singapore, because of HIV travel restrictions. But then my status was discovered while I was applying for a work visa, and I was banned from the country. It was then, after my worst fear had come true, that I finally realized, okay, well, there’s no point in hiding anymore. Let’s do something about this.

Because as much as we have allies, as much as we have HIV-positive straight men and women speaking publicly about the needs of HIV-positive people, I think that the story of being gay and HIV positive is incredibly important. But unfortunately we don’t see enough gay men or trans men and women speaking openly about being HIV positive. And so with the benefits of my partner and my family being 100% supportive, and having learned about my rights by working in the HIV response across Southeast Asia, I felt empowered to speak up.

The first time I spoke publicly was at the AIDS Candlelight Memorial in Manila in 2011, and then it just went from there. And part of the reason I kept on doing it was that people would come up to me and say, “You’ve given me hope by speaking up. You made me feel that I’m not alone.” And because I am now a vocal HIV activist and am able to contribute to the HIV response in Singapore, I was able to appeal for entry on a special case basis and my appeal was granted.

TA Report: How is B-Change using technology and social media to reach young MSM and transgender individuals with HIV information?

Garcia: In the past, I think most public health advocacy work done online has used social media and the Internet as a mass media distribution channel to send messages out to many, but as a one-way conversation. So we’re still playing catch-up to what the private sector has done with social media, through sites like Facebook and Twitter.

At B-Change, we are trying to explore what else could be done with these new technologies by maintaining engagement with target audiences or target groups over a longer period of time and giving them information in a format that is most meaningful to them. And we are getting increasingly better at motivating people to go from online action to offline action, meaning, in this case, taking up HIV testing or adhering to treatment or staying in the continuum of care.

Over the last year, we’ve been beta testing our interventions, and we have formative data that tells us that young LGBT people and HIV-positive MSM see these types of online services as a need that they’re looking for. This month, we’re starting to scale up our peer support web apps so we can promote them in five cities across Southeast Asia—Bangkok, Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, and Manila—and validate these theories.

TA Report: How are the platforms you’ve developed through B-Change helping community-based advocates and organizations grow and learn from one another?

Garcia: In addition to improving linkages to HIV services, we are also developing web-based tools that can help community-based organizations (CBOs) and service providers strengthen the quality of their online outreach. We’ve been doing consultancy for the past four years, but starting this year, we’re providing much more robust tools to help CBOs and service providers improve their capacities by connecting and sharing knowledge with their peers.

We’re focusing on the Asia-Pacific because it’s where we come from and can have the most impact, but we are also sharing our services and what we know with organizations in other developing regions, such as the Middle East, North Africa, and Latin America. I think South-South collaboration allows people with common experiences who understand the environments that we live in—as opposed to people from the West—to work together to improve our communities.

TA Report: As a global ambassador for the ‘Here I Am’ campaign, how did you work to encourage nations in general, and the Philippines in particular, to prioritize support for the Global Fund to AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria?

Garcia: The ‘Here I Am’ campaign is an initiative of the Global Fund Advocates network, and their primary mission is to make sure that we have a fully funded Global Fund. As an ambassador for the campaign, my job was really just to humanize the whole debate and speak about the fact that I’m alive because I have access to HIV treatment and services, and what this and the Global Fund mean for my community.

Ambassadors are deployed to speak in parliaments, the European Commission, or others places where decisions are being made about funding the Global Fund. And time and time again, I heard that when all of the technocratic speak had ended, the thing that really sealed the deal and ensured support was the ‘Here I Am’ ambassador—which just goes to underscore the power of stories in advocacy work.

Laurindo Garcia speaks during a plenary session at the 2014 International AIDS Conference in Melbourne, Australia.

TA Report: How do you think the Global Fund and other large donor institutions could manage their funding to improve local and national responses to HIV among key populations?

Garcia: We need to ensure that the funding goes to where the epidemics are and to the people who are in greatest need. And around the world, we’re still seeing the greatest rise in infection rates among MSM and trans people. We’re also still seeing a rise in rates among sex workers, people who inject drugs, prisoners, and other people at the margins of society.

And if we’re going to make sure that funds are getting to these key populations, then we need to improve the data we’re collecting about them on the ground. For example, we’re not getting disaggregation data on MSM and transgender people, and that’s a key thing that needs to change. Another thing is better ensuring that community groups are being strengthened. Because if there is still lingering resistance to acknowledging or providing services to key populations, there are going to be certain discrepancies in the quality of the data—and who better to be a watchdog than the communities themselves?

Plus, we’ve still got a long way to go for community-based care to be fully integrated into health responses. We know there’s a lot of resistance coming from ministries of health and doctors who don’t want to let go of the reins or make adjustments to regulatory environments to enable community-based care. And yet, in the cases where community-based care is available, the LGBT community reports that these are the best-quality services available.

TA Report: What’s next for B Change and your advocacy work?

Garcia: At B-Change, we’re currently increasing our capacity and partnerships to improve our ability to scale up our online services. The other big thing on our advocacy agenda is improving adolescents’ and young people’s access to services. The message needs to be made loud and clear that adolescents have a right to health and sexual rights, so that young people, including young LGBT, are able to seek sexual health services and testing for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) without the consent of their parents. As an example of why we need this, in the Philippines, the legal age of consent is 12, but you have to be 18 to get an HIV test. So in 2013, we started a five-year strategy called Connecting the Dots to engage and empower young people in the region.