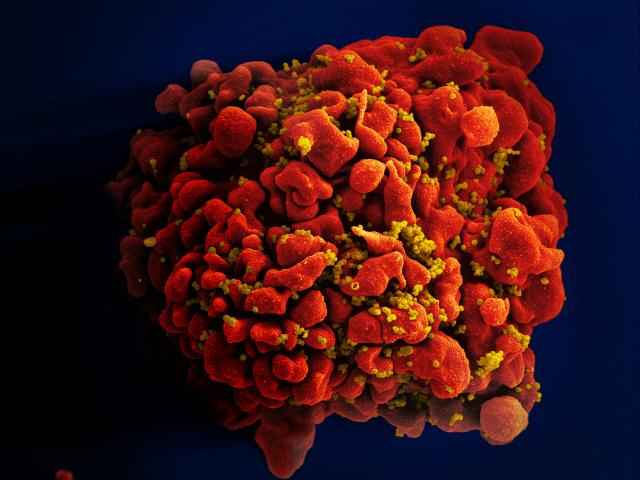

A human T cell infected by numerous HIV particles. (Source: NIAID)amfAR-funded researchers have shown that the reservoir of latent HIV—a major impediment to eradication of the virus—is much smaller in those individuals started on antiretroviral therapy (ART) early after infection. Two groups of amfAR-funded researchers now address why early ART might have such an impact and what might be needed to boost a person’s own immune system to facilitate further destruction of these reservoirs.

A human T cell infected by numerous HIV particles. (Source: NIAID)amfAR-funded researchers have shown that the reservoir of latent HIV—a major impediment to eradication of the virus—is much smaller in those individuals started on antiretroviral therapy (ART) early after infection. Two groups of amfAR-funded researchers now address why early ART might have such an impact and what might be needed to boost a person’s own immune system to facilitate further destruction of these reservoirs.

Writing in the January issue of Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS, Dr. Nicolas Chomont of the Vaccine and Gene Therapy Institute in Florida, and associates from the U.S. Military HIV Research Program and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, note that the HIV reservoir is probably established in long-lived CD4+ T memory cells within the first three days post-infection. Furthermore, early initiation of ART has a much greater impact in limiting these reservoirs than later initiation of treatment. But regardless of timing, these latently infected cells are still there. The authors conclude that “additional interventions will likely be required to eliminate all cells capable of producing virus.”

Led by Dr. Robert Siliciano at Johns Hopkins University, a team of researchers working collaboratively under the auspices of the amfAR Research Consortium on HIV Eradication (ARCHE) has a clear concept of what those “additional interventions” should be. Reporting in the prestigious journal Nature, Siliciano’s group, including colleagues from Yale University, the University of California-San Francisco, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, focuses on the killer T cell. As its name implies, the CD8+ T cell serves to destroy damaged cells (e.g., those with cancer or viral infections, including HIV). But CD8+ T cells can only kill if they see and recognize pieces of the virus within a cell. Unfortunately, via its ability to mutate rapidly, HIV is constantly escaping detection by the immune system by presenting a different face to these killer cells. The flu virus does something similar, though at a much slower pace, leading to the need for different vaccines with each new flu season.

This constant change in the so-called antigenic character of the virus is a major problem given that a predominant strategy for destroying the HIV reservoir is to shock virus out of its dormant state and rely on these killer cells to eliminate the cells from which the virus emerges. Siliciano and associates found that unless ART is started very early—within three months of infection—more than 98% of latent viruses carry “escape mutations” rendering most of the person’s killer T cells unable to detect and kill the infected cells.

The good news is that all of the 15 people in the study who had started ART later on, in the “chronic phase” of their infection, had at least some killer T cells, after they were amplified, that were capable of destroying infected cells. The authors concluded that “appropriate boosting of this response may be required for the elimination of the latent reservoir.”

Dr. Laurence is amfAR’s senior scientific consultant