Dr. Praphan Phanuphak is the founder of the Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre (TRC-ARC) and the co-director of its HIV Netherlands Australia Thailand Research Collaboration. In 1985, he diagnosed the first people living with HIV in Thailand, and has been at the forefront of the national HIV response ever since. In 2001, he was a founding member of the TREAT Asia network. He is currently professor emeritus of medicine at Chulalongkorn University, and a member of the World Health Organization Strategy and Policy Committee on HIV and the UNAIDS Scientific Advisory Committee.

TREAT Asia Report: How did you get involved in the field of HIV/AIDS?

Dr. Praphan: In late 1984, a patient was referred to me in order to evaluate why he had recurring skin infections. In February 1985, he came down with pneumocystis pneumonia. He had a history of male-male sex risk behaviors, and his clinical manifestations, together with some immunological tests that I did, confirmed that he had a very bad immune deficiency problem. I diagnosed him as having AIDS. At that time, the HIV test wasn’t available.

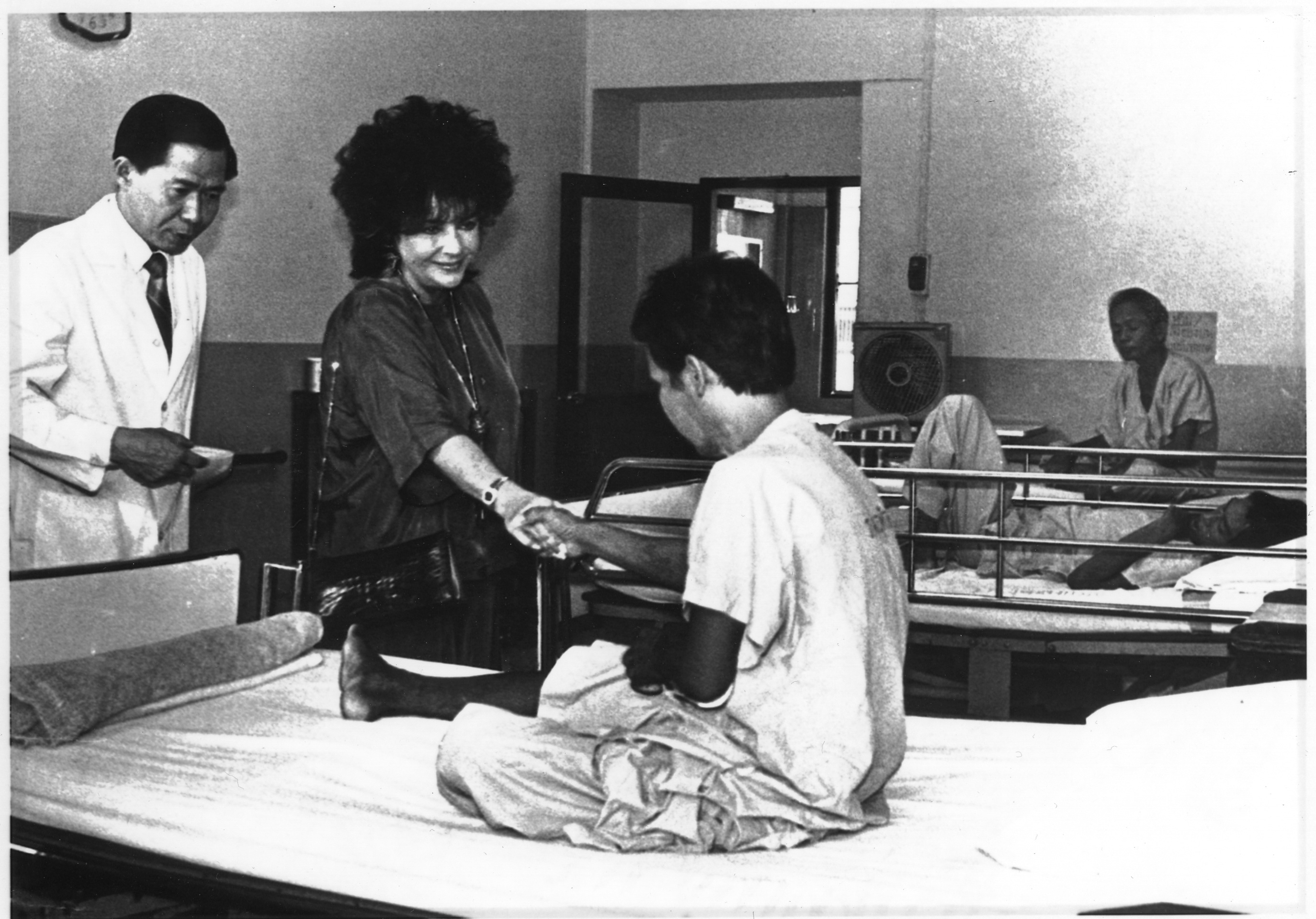

Dame Elizabeth Taylor, amfAR founding international chairman, and Dr. Phanuphak visit a patient living with HIV in Bangkok in 1989. Photo: Bangkok Post © Post Publishing Plc.

In the same month, another person was referred to me to investigate why he had disseminated cryptococcal infections throughout his body. With his history of being a male sex worker, as well as an abnormal immune status, I also diagnosed that he had an HIV infection or AIDS. His girlfriend also had some abnormal lymph glands in her body, and slightly abnormal T-cell function. So I said these three people had HIV infections, and the blood tests confirmed later in the year that they all had HIV. Since that time I have been involved in HIV medicine.

TREAT Asia Report: Can you share with us about Elizabeth Taylor’s visit to meet you and your patients in Bangkok in 1989? How did that come about and what was the impact of her visit?

Dr. Praphan: At that time, Princess Chulabhorn (of Thailand) was interested in organizing an International AIDS Conference in Bangkok. So Her Royal Highness invited many speakers, including Elizabeth Taylor, to come for this conference. Elizabeth Taylor heard about a patient at my hospital who was infected with HIV after receiving a transfusion of infected blood. That was before the national blood bank started screening all donated blood.

We were trying to destigmatize HIV/AIDS, but how successful we were we just wonder.

I invited Liz Taylor to greet this patient to give him some encouragement, because his employers knew about his HIV infection and had fired him from his job, and his family had been evicted from the place where he lived. So Elizabeth Taylor visited him in front of a lot of media. The news came out, which told the public that an HIV-infected person is not someone that you have to be afraid of or condemn, and that people can become infected because of a blood transfusion. We were trying to destigmatize HIV/AIDS, but how successful we were we just wonder. This patient’s case immediately triggered the Thai Red Cross National Blood Center to screen every unit of blood.

TREAT Asia Report: Thailand has become a leader in global HIV cure research. What is your perspective on what is needed to achieve a cure or long-term remission in the foreseeable future?

Dr. Praphan: The Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre is very proud that we are part of that effort. We are currently working with the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Science (AFRIMS—a joint Thai-U.S. initiative) to identify patients with early HIV infections.

We hope that with early treatment, the reservoirs of the virus in the body will be small, and perhaps after a certain period of ART you can stop treatment altogether or boost it with other methods.

Over the last six or seven years, we have found more than 400 cases in which the conventional serology was negative, but the nucleic acid test was positive—results that indicate an early infection. These patients are invited to begin immediate treatment. This is probably the world’s largest acute HIV cohort so far. We hope that with early treatment, the reservoirs of the virus in the body will be small, and perhaps after a certain period of ART you can stop treatment altogether or boost it with other methods such as vaccines or immunomodulators. The wish is that with this kind of approach, people with HIV can be cured or can stop taking ART at least for several years.

TREAT Asia Report: What were the keys to Thailand’s success in eliminating mother-to-child transmission?

Dr. Praphan: The basis is the good infrastructure of the Thai public health service—including antenatal care—and its interest in stopping mother-to-child HIV transmission. The Thai royal family has also played a very important role. In 1996 I asked Princess Soamsawali to give the Red Cross a sum of money to set up a PMTCT [prevention of mother-to-child transmission] fund to provide free ARV drugs—at that time AZT—to HIV-infected pregnant women throughout the country. This program led the Thai Ministry of Health to set up its own PMTCT program. The “Princess Soamsawali regimen,” or Thai Red Cross regimen, was changed in 2004 to three drugs, and the Thai government changed its own PMTCT regimen to three drugs six years later.

At the TREAT Asia Network Annual Meeting October 2017, Bali, Indonesia (left to right): Dr. Thida Singtoroj, TREAT Asia; amfAR trustee Dr. Mervyn Silverman; Dr. Praphan Phanuphak; Dr. Jutarat Praparattanapan, Research Institute for Health Sciences (RIHES), Chiang Mai University; Wilai Kotarathititum, RIHES; Ms. Tor Petersen, TREAT Asia; Dr. Romanee Chaiwarith, RIHES

More than 7,000 pregnant women throughout Thailand have received this regimen, saving hundreds of newborns from HIV infection. So the efforts of Princess Soamsawali and the Thai Red Cross, along with the intention of the government and NGO response, enabled Thailand to end MTCT.

TREAT Asia Report: Despite the country’s progress in HIV prevention, men who have sex with men and other key populations continue to become infected with HIV at disproportionate rates. What else can be done to reduce these rates of infection?

Dr. Praphan: We know which people are most likely to be infected with HIV in Thailand, and we know how to stop transmission and end AIDS in all populations in all countries. You need to test early and treat early, as well as employ preventative methods such as PrEP for those who test HIV negative but have risk behaviors. However, in order to find people for treatment, in order to find high-risk HIV-negative people for PrEP, you need to know who they are and recruit them for testing.

The facility-based approach is very difficult to make work for people in many key populations such as MSM, transgenders, and people who inject drugs. They don’t want to walk into the hospital to seek HIV testing because of the barriers or stigma preventing them from doing so.

In order to find people for treatment, in order to find high-risk HIV-negative people for PrEP, you need to know who they are and recruit them for testing.

We are working to empower community health workers who are very close to these groups of people already—because they are their friends or colleagues—to recruit them to drop-in centers or healthcare centers to have HIV testing, and if they test positive, to take them to the hospital, or if they test negative, to recommend PrEP. This kind of key population-led health service approach is very important, not just for MSM and transgenders but for people who use drugs and other groups as well.

Thailand has been successful in piloting this approach, because although it is not yet legal for lay people to do HIV testing, it is being done under a Thai Red Cross implementation research project with approval from an IRB (institutional review board). We don’t know yet if it will be sustainable in the long run. Beginning this year, with the next round of Global Fund funding, Thailand will extend community-led or key-population-led health services into many more provinces, to reach people who inject drugs and sex workers. This type of approach is a global trend, recommended by the WHO and UNAIDS, and it’s also the national need. We hope it will be accepted by health professionals.

TREAT Asia Report: How can the use of PrEP be expanded in key populations in the region?

Dr. Praphan: Most people in our region believe that PrEP works, and want to know how to implement a successful program. Countries need to conduct implementation research to decide for which individuals PrEP is appropriate, who the prescribers should be, and if the drugs can be provided free of charge.

TREAT Asia Report: What do you think have been TREAT Asia’s most important contributions to the HIV/AIDS response in the Asia-Pacific?

Dr. Praphan: TREAT Asia, under amfAR, has called for international attention to the HIV/AIDS situation in the Asia-Pacific, rather than just on the African continent. Asia has the second largest HIV/AIDS epidemic in the world, but in the past we did not receive much attention from the international community.

TREAT Asia has also worked to gather together medical doctors and scientists in the Asia-Pacific region to do research on HIV/AIDS care and treatment in the Asia Pacific, and to share best treatment knowledge with each of the region’s countries. Now TREAT Asia is expanding the prevention effort, so this will be another important contribution.

TREAT Asia Report: Do you think you can ever retire?

Dr. Praphan: I have asked this question myself many times as now I am 72. I intend to retire. I just need to help someone to succeed me. One of my colleagues is preparing to take over my role in the next few years.