Members of the Delhi Network of Positive People protest the RCEP free trade agreement.

By Lucile Scott

In 2002, approximately 95% of the world’s HIV-positive people lived in developing countries; however, less than one percent of them—300,000—had access to antiretroviral (ARV) therapy. Although ARVs had hit markets in developed nations in 1996, their price tag of $10,000 to $15,000 per person per year put them out of reach of most of the world’s people and governments.

In 2003, despite pressure and threats of sanctions from the U.S. and other Western nations, Indian generic drug companies began producing and exporting generic versions of patented ARVs. Today, nearly 12 million people living with HIV in the developing world have access to these lifesaving medications, and after a decade of competition between generic companies, the cost of a year of first-line ARVs has dropped to as little as $70. India, now known as the “pharmacy of the developing world,” produces 80% of all ARVs used in developing nations.

“Before 2004, we saw many of our colleagues dying because there was no medicine available in the subcontinent, but in Western countries, developed countries, people were accessing it and were able to survive,” says Vikas Ahuja, president of the Delhi Network of Positive People (DNP+). “After that, people in India were able to survive as well.”

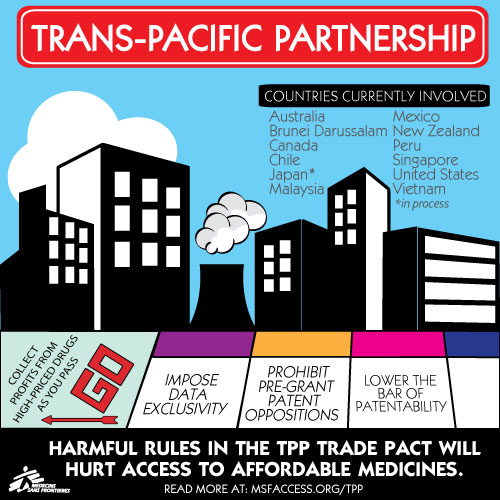

Two new free trade agreements (FTAs) could threaten this critical access to medicines in India and throughout the world: the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), currently being negotiated by 16 countries in the Asia-Pacific,1 and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, being negotiated by 12 Pacific Rim countries.2 Both are projected to wrap up negotiations this year.

While these proceedings are conducted in secret, WikiLeaks has leaked two TPP drafts—the first in November 2013 and the second in October 2014—that reveal that the U.S. is proposing what would be the strictest intellectual property (IP) provisions contained in any U.S.-led free trade agreement in history. Leaked draft text from RCEP reveals that Japan, also a member of the TPP, and South Korea are pushing for similarly strict IP provisions that would not only threaten access to generics in all participating RCEP nations, but also stifle India’s generic industry, threatening access worldwide.

“We are looking at pretty serious consequences for our ability to end AIDS in our lifetime. Government protected monopolies are not what free trade is supposed to be about,” says Peter Maybarduk.Encompassing 40% of the global economy, the TPP would become the world’s largest trade agreement if approved by all negotiating countries, and it has been touted by the Obama administration as a model for future FTAs. The proposed RCEP IP provisions provide an example of the precedent’s possible influence on other future FTAs.

Because newer ARVs are still under patent and only sold at high prices by the patent-holding company, many low- and middle-income countries in the Asia-Pacific do not have broad access to simplified treatment regimens that have fewer side effects or to the second- and third-line ARVs that are critical to the survival of those who have developed resistance to first-line medications. The proposed FTAs would further extend current patent monopolies and delay the entrance of these and other new, lifesaving generic drugs into developing markets—including those for other diseases like hepatitis C that impact millions living with HIV who have both infections. In addition, proposed data exclusivity provisions could potentially cause some generic drugs already in circulation to be withdrawn from the market.

“We are looking at pretty serious consequences for our ability to end AIDS in our lifetime and achieve an AIDS-free generation,” says Peter Maybarduk, director of Public Citizen’s global access to medicines program. “It will be hard to get there if second-, third-, and potentially fourth-line ARV treatment is priced too high to afford. We need to increase generic competition to drive down prices, not reduce it by granting patent monopolies—government protected monopolies are not what free trade is supposed to be about.”

An MSF poster about the negative impacts of the TPP.

Public Health vs. Commercial Interests

In 1994, members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) signed the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)agreement, which imposed minimum global patent and IP standards for the first time. The document also provided certain flexibilities, including the ability to issue compulsory licenses to allow production of patented products, so that governments could balance their citizens’ health needs with corporations’ commercial interests.

Drug patents are designed to spur innovation by ensuring that companies can recoup the cost of research and development (R&D) and earn a profit on their inventions. However, most pharmaceutical companies spend far more on marketing than on R&D, and they report some of the highest global profit margins of any commercial industry.

Since 1995, U.S.-led trade agreements have incrementally rolled back those internationally agreed upon flexibilities through provisions known as TRIPS-plus. The TRIPS-plus provisions proposed by the TPP and RCEP would slow the approval of generic medicines through data exclusivity provisions, extend certain patents beyond the current standard of 20 years, allow re-patenting of older drugs with minor modifications, and enact border measures permitting the seizure of generic drugs transiting through treaty member states to other destinations.

“Governments would be required to change their laws to comply with the TPP, and if they are seen to be in breach they would be exposed to lawsuits worth hundreds of millions of dollars,” says Fifa Rahman, policy manager at the Malaysian AIDS Council. “This interference with domestic regulation is a new form of colonialism.”

The leaked TPP text reveals that, with the exception of Japan and occasionally Australia, member nations have remained staunchly opposed to these U.S.-proposed TRIPS-plus provisions in the TPP. However, the treaty has been under negotiation for five years, and negotiations that took place in Hawaii in early March were likely the last technical round. After that, negotiations will move on to the ministerial level. “The IP negotiators are saying the proposals are not in line with international law and will delay access to meds and innovation, but the ministerial positions may be different,” says Judit Rius, U.S. manager of the Access Campaign for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). “We will see which countries maintain opposition and which give it up for market access.”

If enacted, these TRIPS-plus provisions would not only threaten the ability of national governments to respond to HIV, but would also impact the response of international programs like the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). In 2014, over seven million (out of a global total of 14 million) people receiving ARVs were receiving them through PEPFAR, and over 98% of the ARVs purchased by PEPFAR were generics.

India’s Patent Law Under Threat

India provides two-thirds of the world’s generic medications. But this generic supply is under threat.India’s Patent Law prioritizes public health over commercial interests and allows the country to sustain its generic drug industry, which provides two-thirds of the world’s generic medications. But this generic supply is under threat—and not only from these multilateral FTAs.

In 2013, the Indian Supreme Court issued a decision denying an application by Swiss pharmaceutical company Novartis for a patent for its leukemia drug Gleevec® on the grounds that it was too similar to an existing drug—a decision that was in full compliance with India’s patent law. Soon afterwards, the U.S. began exerting direct bilateral pressure on India to reform its patent system, placing India on the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative’s Priority Watch List. Then in September 2014, India’s Prime Minister established a bilateral U.S.-India IP working group and stated that his government would accept any of the group’s suggestions regarding India’s current IP regulations.

“Previously India has taken a strong position that its patent laws are well in line with TRIPS, and it doesn’t need to accept any TRIPS-plus provisions beyond this, but things are changing with the new government,” says Shailly Gupta, policy advocacy officer at the MSF Access Campaign in New Delhi. “They are more willing to put us in alignment with TRIP-plus provisions to ensure more foreign investment in the country.”

‘The Middle-Income Country Curse’

The World Bank determines countries’ income level based on average per capita income, without looking at income inequality. As a result, 70% of the world’s poor now live in countries categorized as middle-income (including India), where governments do not cover the cost of many medications—putting patented drugs completely out of reach of all but the wealthiest individuals. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 100 million people fall into poverty every year due to the already high cost of medications and healthcare.

Draft text of the TPP includes extensions that would allow low- and middle-income member countries3 to delay compliance with certain TRIPS-plus provisions. However, many advocates contend that even extensions will make little difference in the long run. “The proposed provisions would issue a blank check to increase the cost of medicines,” says Rius. “It doesn’t matter if you wait five or 10 years. At the end of the day it is going to hit the public health system of countries that cannot afford it.”

While low-income countries’ treatment programs for HIV and certain other diseases are often supported by international donors, financial aid frequently declines as countries graduate to middle-income status.

This has been the experience of Vietnam, which was classified as a lower-middle-income country in 2012. According to a new study examining the impact of the TPP on Vietnam’s national HIV program, if the 2014 provisions are implemented, they could drive up drug prices just as Vietnam is preparing to take over its own HIV response, causing national ARV access to decline by more than half—from 68% to just 30% of eligible patients.

But none of these measures can be enacted if negotiating governments do not agree to the terms. “Trade ministers need to ask, ‘How much is market access worth to us?’” says Maybarduk. “And treatment advocates and people in developing countries need to continue to provide pressure to ensure that all TRIPS-plus provisions are removed from these agreements. Otherwise they will lead to preventable suffering and quite likely death.”

1 RCEP currently includes Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam

2 The TPP currently includes Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the U.S., and Vietnam

3 The low- and middle-income countries currently included in the TPP are Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, and Vietnam.