This March, news broke that a child

from Mississippi, who tested HIV

positive at birth, had been cured of HIV.

Less than two weeks later, researchers

reported that 14 individuals in France

had been functionally cured of the

virus. Five years ago, the first case of

a cure occurred in an HIV-positive man

with leukemia, known as the Berlin

patient. “A decade ago, almost nobody

spoke of curing HIV infection as a

realistic goal, yet we find ourselves in

early 2013 with not one, nor even two,

but three different types of HIV cure,”

said Rowena Johnston, Ph.D., amfAR

vice president and director of research.

[Update (7/10/14): Surprising New Development in "Mississippi Child" Case]

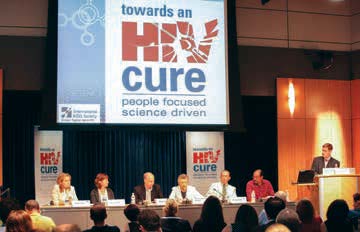

Dr. Rowena Johnston (second from left) participated

in a two-day pre-International AIDS Conference cure

symposium in July 2012.

So what does this all mean?

According to Johnston, “Much

depends on how a cure is defined.”

Experts currently define two categories

of HIV cure. A sterilizing cure requires

the complete eradication of all HIV from

a person’s body. A functional cure

requires only that even after patients

stop antiretroviral therapy (ART), their

HIV remains in remission and does

not damage their immune system

enough to cause any adverse health

consequences.

So what does this

all mean? According

to Johnston, ‘Much

depends on how a

cure is defined.’

The French cases, known as

the VISCONTI cohort, are viewed

as functional cures. These patients

began receiving ART within the first few weeks after they became infected, a

time known as acute infection. Today

they still have detectable HIV in their

blood, but have been off ART for an

average of seven years without any

signs of disease progression. However,

the researchers noted that only 10–15

percent of patients who are identified

during acute infection and placed

on immediate treatment can expect

similarly controlled infections.

It remains less clear whether or not

the Berlin patient and the Mississippi

child experienced functional or

sterilizing cures. Trace amounts of

HIV have been sporadically detected

in both patients since they went off

treatment, but at such minimal levels

that the tests could represent falsepositive

results. In addition, research

done to date has not identified virus

in either patient that is capable of

replicating, and therefore whatever is

present does not appear to be causing

harm to the patients.

"This case has

galvanized discussion

about the potential for

immediate treatment

of HIV-exposed infants

to increase the chance

of curing them in the

future."

The Berlin patient was cured after

he received a stem cell transplant from a donor with a very rare

genetic resistance to

HIV infection, a lifethreatening

and costly

process that cannot

be recommended on

a wide scale. The

Mississippi child, on

the other hand, was

placed on ART at 31

hours after birth, before

confirmation of HIV

infection, an unusual

approach that is not

routinely practiced in

the U.S. or in other

countries. After 18 months of treatment,

it was stopped and has not been

restarted for over a year.

This was an unusual and unexpected

outcome that further research will help

to explain. Nevertheless, this case has

galvanized discussion about the potential

for immediate treatment of HIV-exposed

infants to increase the chance of curing

them in the future. “The case is a startling

reminder that a cure for HIV could come

in ways we never anticipated,” said

amfAR CEO Kevin Robert Frost.